Regular safety inspections are often legally mandated by workplace safety regulations, but they are also an excellent way to reinforce a culture of safe work practices. Safety inspections are opportunities to train staff about safety awareness and encourage a team approach to minimize workplace hazards.

The cornerstones of a comprehensive workplace safety program are the safety inspectors and the reports they write. Thorough safety inspection reports are an indispensable compendium of shared information that coordinates the actions of management and employees to cooperatively strive for a safer workplace.

Pro Tip

Take your safety inspection forms on the go with Jotform’s mobile forms — free and available offline.

Elements of a useful safety inspection report

There’s an infinite variety of workplaces, each with hazards peculiar to the type of work and the behavioral patterns of the people working there. The best safety inspectors know the jobs they’re evaluating, are competent with the necessary tools, and genuinely understand the hazards.

Whether you’re inspecting a university laboratory, a metal-stamping plant, or a busy warehouse, there are certain elements required to write a useful safety report.

Comprehensive recordkeeping. Workplace safety programs require comprehensive records of any safety lapses in the work area being inspected. Consult all available incident reports to familiarize yourself with documented problems.

Strive to be comprehensive in your own report. Ask employees informed questions to gather all the information you need.

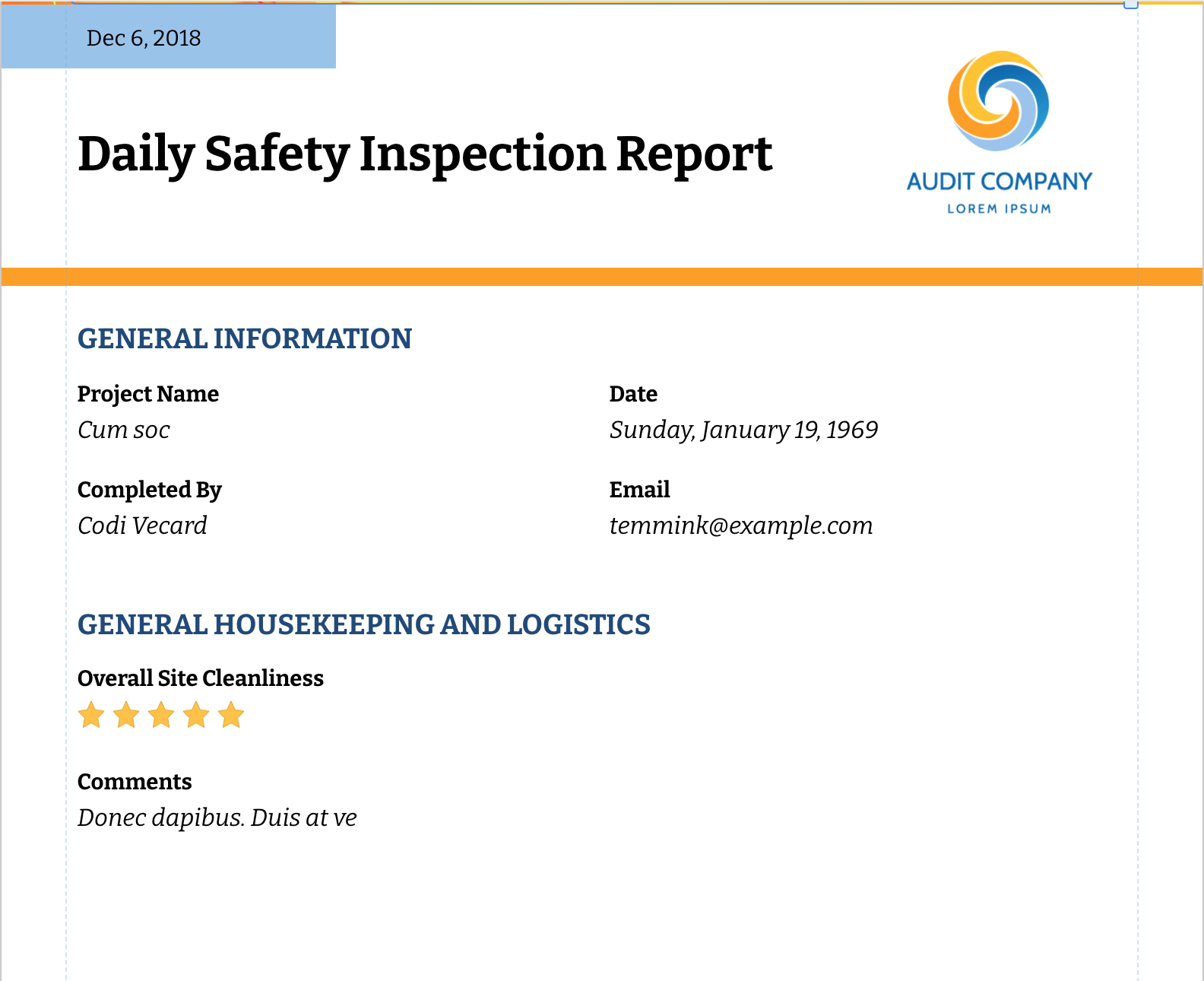

Use a checklist, like the Jotform template for safety inspections, to both prepare for your inspection and to record all the information you gather. Check on past problems noted in previous inspections to make sure they have been addressed.

Data analysis. Familiarize yourself with all documented procedures and work practices, as well as all equipment. Compile all comments, recommendations, and corrective actions taken.

Does the work area you inspected comply with all regulatory requirements and industry best practices? Are all required licenses and safety certifications properly displayed, if required?

State whether you’re confident that employee training is sufficiently focused on safety, and make recommendations if you aren’t convinced it is. The inspection report must concisely distill this mass of data to guide follow-up actions.

Cite good practices. Don’t get caught in the mental trap of looking only for what’s wrong and taking for granted what’s right. Note all teams and managers who are doing their jobs safely in scrupulous compliance with all rules and regulations.

Inspections might require you to work in remote areas or confined spaces with unreliable internet. Jotform Mobile Forms is designed to help you record your observations even when you’re offline.

Accidents are bad for the bottom line

Workplace injuries are a huge burden for business. The National Safety Council estimated the total cost of work injuries in 2019 was $171 billion.

Lost wage and productivity totaled $53.9 billion, medical expenses were $35.5 billion, and administrative expenses amounted to $59.7 billion. The cost to employers not covered by insurance was a painful $13.3 billion, including the value of time lost by workers and the cost of time required to investigate injuries, write up injury reports, and so forth.

What’s harder to calculate is the cost to team morale when someone is injured, and the strain on company culture when employees don’t trust management to maintain a safe workplace. On the other hand, there’s a famous example of an unblinking focus on safety driving profits.

Paul O’Neill was appointed CEO of Alcoa in 1987 when the aluminum maker headquartered in Pittsburgh was an aging industrial titan. O’Neill decided from his first day on the job to make safety the key metric for judging company performance.

When he introduced himself as CEO in October 1987, he baffled and unnerved his audience of Wall Street money managers, investors, and bankers focused on market share, overhead, stock price, and reliable dividends.

“I want to talk to you about worker safety,” O’Neill began. “Every year, numerous Alcoa workers are injured so badly that they miss a day of work.”

O’Neill noted that Alcoa already had a better safety record than the norm in the industrial sector but that his central effort as CEO would be to continually improve workplace safety. “I intend to make Alcoa the safest company in America. I intend to go for zero injuries,” he said.

Based on audience questions, they didn’t take him literally. When a couple of investors asked about inventories and capital ratios, ignoring what O’Neill had said about safety being the central performance metric, he basically cut them off.

“I’m not certain you heard me,” O’Neill said. “If you want to understand how Alcoa is doing, you need to look at our workplace safety figures. If we bring our injury rates down, it won’t be because of cheerleading or the nonsense you sometimes hear from other CEOs. It will be because the individuals at this company have agreed to become part of something important: They’ve devoted themselves to creating a habit of excellence. Safety will be an indicator that we’re making progress in changing our habits across the entire institution. That’s how we should be judged.”

Many investors reportedly sold their Alcoa stock immediately following the meeting and encouraged their clients to sell too. They should have trusted O’Neill. When he left Alcoa in 2000, the company’s income was five times higher than when he’d started. Alcoa’s market value had increased from $3 billion to over $27 billion. His focus on safety had energized employee engagement at every level, from the foundry to the C-suite.

It’s more than checking boxes

Phil La Duke, a celebrity in the workplace safety industry known as “the safety iconoclast,” warns against overreliance on safety checklists. Look first, then consult the list on a second walkthrough, La Duke advises. The interactions of humans in a hazardous work environment are too random for a list to contain everything that needs to be noted and adjusted.

“Use the checklist to confirm the absence of hazards after you have walked the area instead of using it to prompt you to look for a hazard,” he wrote. “This may sound like a trifling distinction, but it may well mean the difference between identifying and correcting dozens of hazards and finding one or two.”

As O’Neill showed at Alcoa, safety is one goal everyone can commit to wholeheartedly. Achieving lofty safety goals encourages open communication and constant re-examination of processes. Well-grounded safety inspection reports are the foundation of a company safety program that drives performance.

Send Comment: